PSTAT 5A: Lecture 20

Inference for Paired Data

Mallory Wang

2024-07-24

Paired Data

Data are paired when each observation in one data set corresponds to exactly one observation in the other data set. This can happen when there are two measurements on each individual in the sample or when there is a natural pairing between the samples (e.g., siblings, spouses, days of the week).

“Studies leading to paired data are often more efficient—better able to detect differences between conditions—because you have controlled for a source of variation (individual variability among the observational units).”

With paired data, we have two measurements on each pair. Instead of being interested in the two measurements separately, we are interested in the differences within each pair. What may originally look like two data sets is actually just one data set of differences.

Example

The Comprehensive Assessment of Outcomes in Statistics (CAOS) test was developed by statistics education researchers to be “a reliable assessment consisting of a set of items that students completing any introductory statistics course would be expected to understand.” When doing research about a particular teaching method, Professor Miller had students take the CAOS test at the beginning of the term (pretest) and at the end of the term (posttest). Why does it make sense to treat these measurements as paired data?

- By examining the differences between the pretest and posttest measurements, we eliminate the variability across different students and focus in on that improvement measure (the difference between the posttest and pretest scores) itself: we have controlled for one source of variation (variability within each student).

Paired Data Procedures

Once we compute the set of differences, we use our one-sample methods for inference. Our notation changes to indicate that we are working with differences.

Our parameter of interest is \(\mu_d\), the populatioon mean of the differences.

The point estimate for \(\mu_d\) is \(\bar{x}_d\), the sample mean of the differences.

Sampling Distribution of the Sample Mean of the Differences \(\bar{x}_d\)

The sampling distribution of \(\bar{x}_d\) will be approximately normal when the following two conditions are met:

Independence: The observations within the sample of differences are independent (e.g., the differences are a random sample from the population of differences).

Normality: When the sample is small, we require that the sample of differences comes from a population with a nearly normal distribution. Thanks to the Central Limit Theorem, we can relax this condition more and more for larger and larger sample sizes.

Sampling Distribution of the Sample Mean of the Differences \(\bar{x}_d\)

The mean for sampling distribution of \(\bar{x}_d\) is \(\mu_d\). The standard error for this sampling distribution is

\[\frac{\sigma_d}{\sqrt{n}}\] where \(\sigma_d\) is the standard deviation of the population of differences and \(n\) is the number of pairs.

Sampling Distribution of the Sample Mean of the Differences \(\bar{x}_d\)

Since we do not usually know the population standard deviation of the differences \(\sigma_d\), we estimate it with the sample standard deviation of the differences \(s_d\).

As soon as we estimate the population standard deviation \(\sigma_d\) with the sample standard deviation \(s_d\), we need to switch from the standard normal N(0, 1) distribution to a \(t\) distribution.

The sample mean of the differences \(\bar{x}_d\) can be modeled using a \(t\) distribution and the estimated standard error \(\frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}\) when each sample mean can itself be modeled using a \(t\) distribution with \(n − 1\) degrees of freedom.

Hypothesis Test for \(\mu_d\)

Based on a sample of \(n\) independent differences from a nearly normal distribution, the test statistic is

\[t = \frac{\bar{x}_d -\mu_0}{\frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}}\] where \(\bar{x}_d\) is the sample mean of the differences, \(s_d\) is the sample standard deviation of the differences, \(n\) is the sample size (number of pairs), and \(\mu_0\) corresponds to the null value of the population mean of the differences, \(\mu_d\).

We use the \(t\) distribution with \(n-1\) degrees of freedom to calculate our p-values.

Confidence Interval for \(\mu_d\)

Based on a sample of \(n\) independent differences from a nearly normal distributioon, a confidence interval for the population mean of the differences \(\mu_d\) is

\[\bar{x}_d \pm t^* \frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}\]

where \(\bar{x}_d\) is the sample mean of the differences, \(s_d\) is the sample standard deviation of the differences, n is the sample size, and \(t^*\) corresponds to the confidence level and n-1 degrees of freedom.

Example

A company institutes an exercise break for its workers to see if this will improve job satisfaction, as measured by a questionnaire that assesses workers’ satisfaction. A random sample of 50 workers was taken. Each worker was given the questionnaire twice: once prior to the implementation of the exercise break; a second time after the implementation of the exercise break. The differences in job satisfaction (satisfaction after implementation of the exercise program minus satisfaction before implementation of the exercise program) were calculated, and the mean of the difference is calculated to be 11.727 and standard deviation of 17.3869.

Solution

- Step 1: Write hypotheses

- Since the company is interested in if exercise break will improve job satisfaction, we can formulate the hypotheses as

\[H_0: \mu_d = 0\] \[H_A: \mu_d > 0\]

Solution

- Step 2: Check conditions

This is paired data so we want to check

Since the data comes from a random sample of workers, we can assume the independence condition is met.

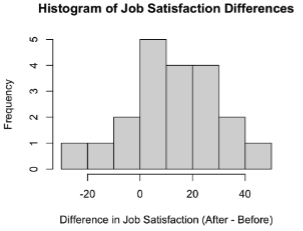

The population of differences is normally distributed. Suppose this is the histogram of job satisfaction differences:

Solution

- Step 3: Calculate test statistic and critical value

\[TS = \frac{\bar{x}_d -\mu_0}{\frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}} = \frac{11.727 - 0}{\frac{17.3869}{\sqrt{50}}} = 4.77\]

For one-tail test with \(\alpha = 0.05\) and \(df = 50-1 = 49\), the critical value \(t_{0.05, 49} = 1.68\).

Solution

- Step 4: Decision

Since this is an upper tail test, we want \[TS > t\] \[4.77 > 1.68\] Therefore, we have enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

- Step 5: Write a conclusion

At the \(\alpha = 0.05\) significance level, we have enough evidence to reject the claim that mean difference in job satisfaction before and after implementing exercise break is the same. This data suggests that the mean difference in job satisfaction after implementing exercise break is greater than that before.